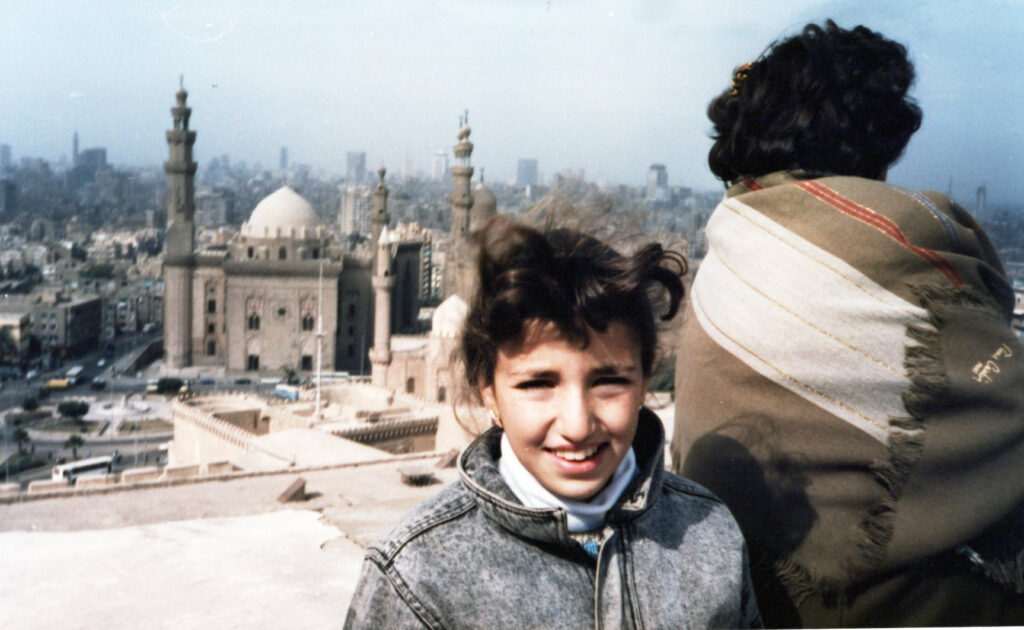

I moved to Cairo at three very different times in my life: as an 11-year-old kid, a 20-year-old college student, and last summer, as a 40-year-old spouse and mother.

One could argue that as an Egyptian American, I should consider Egypt my “homeland.” But as a Xennial born and raised in California, Egypt felt nowhere near home in the early ’90s, when my parents told me and my brothers that we would be moving there.

I vigorously protested. Miss middle school? Make new friends? Learn Arabic? Leave our house in idyllic Manhattan Beach to live in an apartment in crowded, noisy, polluted, chaotic Cairo? On the Gupte Scale, this move was a 9/15: 2 for timing, 3 for destination, and 4 for resources.

But my dad, a college professor, had been granted a sabbatical — and my parents, who had never expected their move to America to be permanent, were determined to use this opportunity to make sure their children didn’t lose touch with our roots. In a way, they were the “trailing parents” more than we were the “trailing kids.”

Their plan had been to stay for one year, but we ended up staying twice as long to fully immerse ourselves in the language, culture, heritage, and family life. (I don’t recall whether I and my brothers were consulted about this extension, but I’m fairly sure we were told it would be for our own good.)

Stumbles and tears

With the benefit of hindsight, I agree that our parents made the right decision. My brothers and I would have otherwise grown up disconnected from our culture, instead of becoming multifaceted, multilingual, and worldly human beings.

That’s not to say the experience was smooth sailing, however. Those two years were an emotional rollercoaster for me and my two younger brothers, having previously only visited Egypt during summer vacations.

Back in California, we had worn casual clothes and walked to school. On our first day of school in Cairo, we dressed in our grey uniforms with stiff white shirts and suffocating ties and boarded separate buses — one for girls, one for boys. At the end of the day, my little brothers arrived home with torn ties and dirt-streaked tears down their faces. “We got in a fight on the bus, but we don’t know how!” they sobbed. They had gotten swept into the chaos, despite quietly minding their own business.

Our private school, Misr Language Schools, taught certain subjects in English (math, science, and English) and others in Arabic (social studies, religion, and Arabic). Considered a “khawaga” (foreigner) by the school administration, I was granted an “exception” for the Arabic classes, which meant I only had to pass — but that in itself was not an easy task, given that I didn’t even know the alphabet.

My parents hired an Arabic tutor who came several days a week and spoke no English, so communication was initially a challenge. When he asked me if I knew what the word “bata” meant, I answered, “Yes, it means duck.” He then asked, “What does duck mean?” “Like, ‘quack, quack’,” I said. At least my answer was correct!

Making friends was also tough. One of the more depressing memories was of my 12th birthday, which we had planned to celebrate with a party that happened to fall on a Friday the 13th. Egyptians don’t necessarily believe in this superstition, but it did turn out to be a bad omen. It rained heavily and only three out of a least a dozen classmates braved the weather and disastrous traffic to come to the celebration.

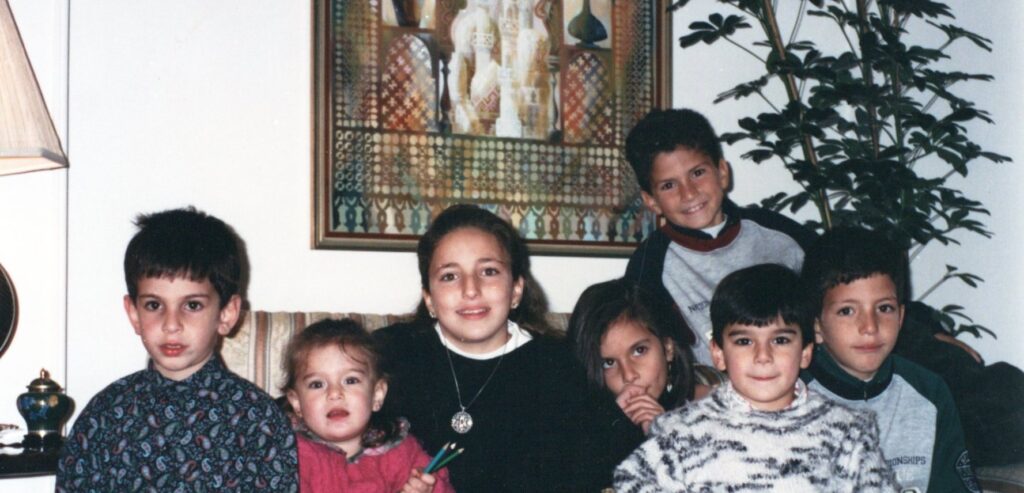

Gradually, things got better. We adapted to Cairo, we learned Arabic, we made friends. I took dance classes, ran my first race ever at the Pyramids, and finished my final exams in the top 10 of my grade — with Arabic included! My parents made the effort to constantly surround us with the extended family, which included grandparents, aunts, uncles, cousins, and more. We loved taking road trips to grandma’s farm, where we would swim in the pool, eat a big feast, and sit for hours on the terrace chatting underneath the shade of the mango tree.

Whenever I look through old photos or watch videos taken during those two years, I have tears in my eyes. In one of my favorites, we’re all smiles, dressed in traditional Egyptian dress during a “galabeya” party on a Nile cruise to Luxor and Aswan with visiting friends from the U.S. We repeated that trip with my dad and grandma in December 2018 — six months after my mom had passed away from cancer.

The trouble with a two-year stint is that just when you’ve gotten used to your new life, it’s time to leave. Our return to southern California gave me my first experience with “reverse culture shock.” This was back in the days before email, so it had been difficult to keep in touch, beyond the odd letter or postcard. My best friend was no longer my best friend; she was now with the “cool crowd” and, as a newcomer, I was not invited. We were entering high school, and I had missed all the transitions the others had made together in middle school.

Forging my own path

Even though I felt like I had to start my life all over again, I didn’t feel bitter. Egypt had found a permanent place in my heart. My family continued to spend summers there, and I kept in touch with the friends I had made during the school year. I also got involved with the Egyptian American Organization in Los Angeles, writing their newsletters and going to the group’s youth events.

After my freshman year at the University of Southern California (USC), my language skills and network helped me land a summer internship at AP Television News in Cairo. I enjoyed writing scripts and reporting on topics like genetic engineering in Egypt’s farms and new archaeological discoveries. The experience laid out the bricks in building my path towards my journalism career.

A year later, as friends were signing up for study abroad programs to Italy, Spain, and China, I chose to forge my own path. Since there was an option to request a country that was not on the usual curriculum, I proposed and was approved for spending my junior year at the American University in Cairo.

What a difference from my time as a trailing kid! This time, I was looking forward to the experience, rather than dreading it; my classes would all be in English and I already had a base of friends to start. I got to go on college trips to Sharm El Sheikh on the Red Sea, ring in the Y2K New Year’s Eve at the Pyramids, and travel to Turkey with my grandma for Spring Break. I joined the nearby Gezira Sporting Club track team and even competed in the 800-meters national championship.

While the year was not without its frustrations, I had an outlet to express them: my weekly column, “Like An Egyptian,” for USC’s Daily Trojan newspaper. Writing helped me find the humor in things like the “IBM” system — which stands for “insha’ Allah” (God willing), “bokra” (tomorrow), and “ma’alesh” (nevermind) — that encompasses Egyptians’ laidback and good-humored, yet fatalistic attitude about everything.

The idea of choosing to live in Egypt long-term still seemed an unlikely possibility, but no longer an intimidating one. Returning to Egypt by choice, as a well-prepared young adult, had taught me to be receptive to cultural differences that I hadn’t fully understood as a kid.

Both experiences energized me for a lifetime of cross-cultural personal and professional opportunities; I felt ready for whatever the world would throw at me. Incidentally, they also prepared me for the hardest task of all: helping my own children adjust to life as trailing kids, too.

Continue reading Part 2 of Nada’s story.