One of the best parts of being a trailing spouse is stitching together an amazing tapestry of friends and family across different corners of the world.

Perhaps the worst part is the cruel distance when you most want to be near them — including when it’s time to say goodbye.

Earlier this year, I lost my dear friend Anne Doll in Seattle to appendix cancer, at the age of 40. Earlier this week, I lost my grandmother in Nicosia, Cyprus, at the age of 104. In both cases, I was thousands of miles away in Delhi, trying to push through my grief and guilt to continue parenting through this pandemic. (Our inability to observe communal mourning rituals during COVID lockdowns, even when mere driving distance away, has surely been a core element of our collective trauma this past year.)

Although I spent years writing for newspapers, including dozens of obituaries, and there’s so much to share about how two heavily-pregnant trailing spouses became fast friends during the hottest Seattle summer on record? I couldn’t bring myself to eulogize Anne. Fortunately, her husband has done that for us all. And, while I can’t be there for her memorial service this summer, at least my family’s absence will provide a few extra bedrooms for her college friends who fly in for the occasion.

For my grandmother, however, given that I missed her funeral by a matter of hours, I thought I could share my thoughts here. After all, she was a trailing spouse, too. (Whenever she had to list the different Cypriot city where each of her three children had been born, the reaction was usually something like, “Lady, did you have to have a kid each time you moved?” I think some of our readers can relate!)

Elli Moussoulidou Stavrinides, 1916-2021

You would think I would be better prepared to write a tribute for my grandmother, but when someone has lived to be 104 years old, it’s difficult to know how to talk about her life. Like the large lace tablecloths Yiayia Elli used to crochet, you have to look very closely to admire the tiny, intricate details, and also step far back to appreciate the symmetry and scope of the entirety.

As I described in an article for The Cyprus Mail on the thrilling occasion of her 100th birthday, she lived through a turbulent century. (To be fair, that could probably describe any period in Cyprus!) Thanks to her incredible memory, we intimately know the history of our family and island alike, going back to September 1916.

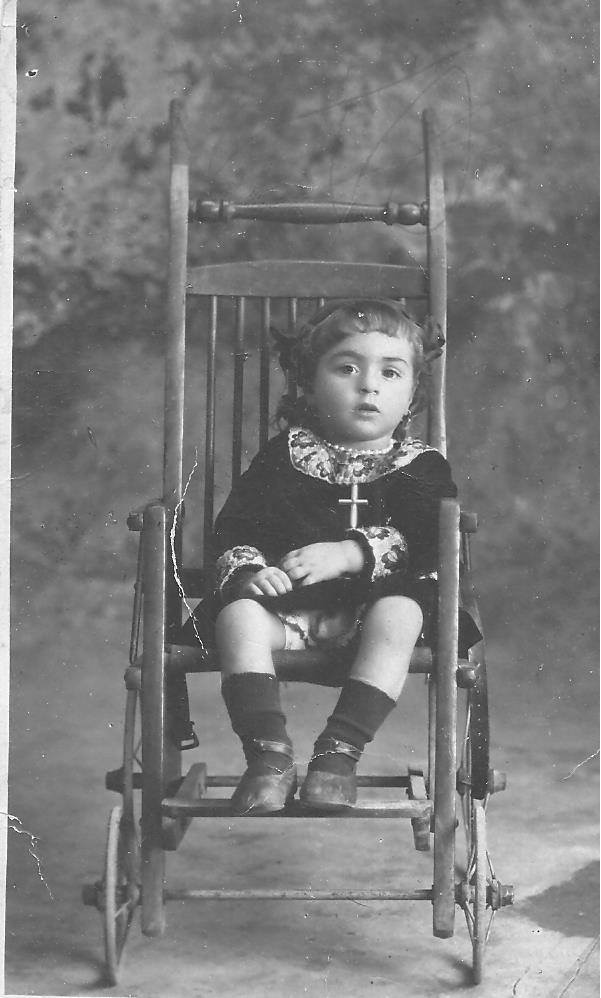

She was born and raised as the second of six children to Savvas Moussoulides, a merchant, and his wife Loukia. They lived in the center of Nicosia during the early years of British rule, back when the city was more like a village, with many more chickens than cars. She proudly earned a teaching certificate with the intention of working at a grammar school, but at that time, an attractive woman from a good family was directed to focus on becoming a wife and mother instead.

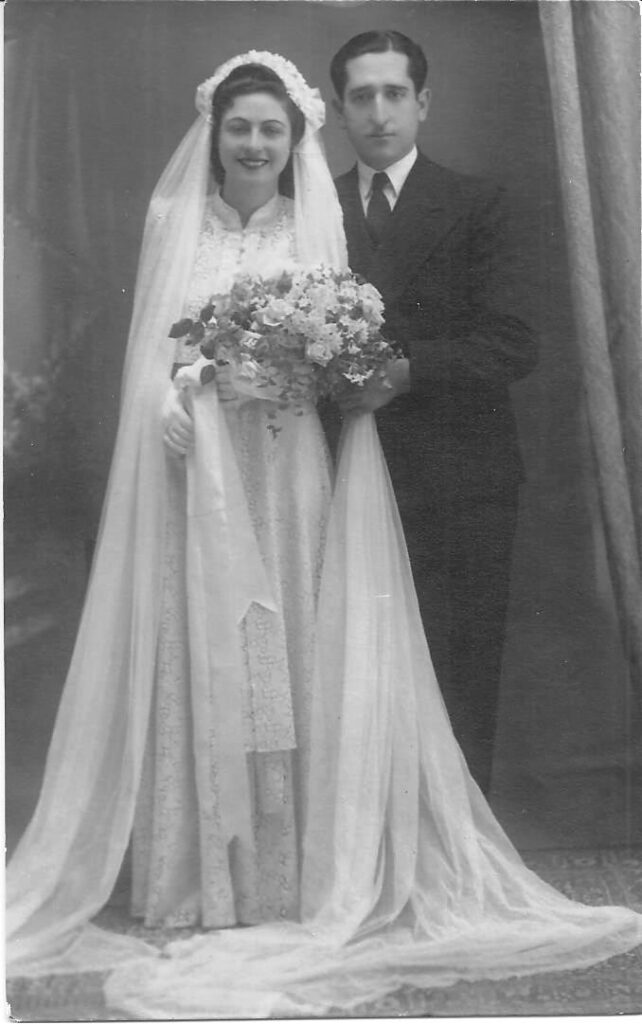

Sure enough, she caught the eye of an eager young lawyer, Andreas Stavrinides. and he eventually convinced her to marry him after he had become a judge. (Family legend states that this was the condition of her acceptance, but she always denied it!)

After their January 1943 wedding, Yiayia Elli and Pappou Andreas spent a decade assigned to various court jurisdictions: Paphos, Larnaca, Kyrenia, Famagusta. They had three children along the way – Zenon and Alkis, then my mother Eva – before returning to Nicosia in 1953, just before the start of the Eoka campaign against the British colonial rule.

Her life didn’t change much after Cypriot independence. They continued summering in the Troodos mountains and dancing at the Dome Hotel in Kyrenia for New Year’s Eve, and her children went to England for their studies. Perhaps it was a bigger transition when Pappou joined the High Court in 1970 and they became guests at state dinners, meeting Raquel Welch and Princess Margaret.

In the violent summer of 1974, with their sons safely studying abroad, she and Pappou focused on getting my mother home from her nearby office and restricting their activities to walking distance. That July, they slept with my mother’s puppy on mattresses under the kitchen table, in case of bombs. During the second stage of the Turkish invasion, in August, they fled to my aunt’s cottage in the Pedoulas mountains, squeezed in with anxious cousins awaiting news of their losses.

These experiences may explain why Yiayia Elli always kept track of current events, religiously watching the evening news and keeping her handheld radio playing under her pillow. Her main focus, however, was on monitoring family updates. She missed her husband’s retirement party to be in America for the birth of her first grandchild — me. When my parents needed funds to buy our house in New York, she sold her own home and moved to a smaller flat. After Pappou’s death in 1991, she traveled less and was happiest spending time with friends and family who had retired back to Nicosia or returned for a holiday visit.

Her earlier training as a teacher was evident in how patient and fun she would be with small children. She was never too tired to play “bicycle,” putting our feet together and pedaling each other until we lost balance by laughing too hard. I remember hours of cooking custard together (and soothing my clumsy burns), reading Heidi cartoons, going for walks, singing songs, teaching me to crochet, and trying to trick me into eating new foods by feeding me in the dark on the porch. Her head was always available for budding hairstylists, and her arms for rocking a baby doll or stuffed animal.

The only sure way anyone could convince Yiayia Elli to do something nice for herself, like getting a new TV, would be to say that it was for her family. As we grew up, she never missed an opportunity to worry about whether we were eating enough, earning enough, or dressed warmly enough. (All three grandchildren — me, my sister Laura, and our cousin Sophia— can do impressions of her urging us to have some lemonade.) In 2002, I tricked her into accompanying me on a 3-day cruise to Egypt by telling her I had won the tickets and didn’t want to go alone. At the ship’s entrance, we discovered that her passport had expired, but the agent took one look at her smart black dress and cane and let us on board anyway!

Yiayia Elli was a “great” grandmother, so it’s only fitting that she lived long enough to become a great-grandmother. In the last 10 years, she got a lot of joy from my children R.J. and Katia: applauding their singing and dancing, throwing and catching balloons with them, and talking to their photographs in between visits.

Many people asked for advice, but she never could explain how she had lived so long. She had a moderate diet, with lots of fresh fruit and vegetables and the occasional glass of KEO beer, and she walked everywhere she broke her leg at age 90. If it’s any consolation, she always said that 90 was the best age to live to, which is conveniently much more realistic for most of us!

From telegrams to video calls, her life spanned 104 years of enormous change, including the Great Depression, two World Wars, the division of Cyprus, the Euro and the “haircut.” She mourned the deaths of her parents, her husband and all but the youngest of her five siblings. She celebrated as both her sons became professors, and the births of three grandchildren and two great-grandchildren.

When we reminisced about these milestones at her 100th birthday party, we couldn’t imagine that she would live through several more major historical events, including Brexit and COVID-19. Yet she stoically took her first vaccination shot earlier this year, and we were making plans to celebrate her 105th birthday in September.

(For my part, I kept trying to get KEO to feature her in an advertising campaign, by sending them photos of her drinking a glass of beer on birthdays!)

It’s not fair that Yiayia Elli has died during the coronavirus lockdown, when we can’t gather together to celebrate her life properly, but her memory will be eternal — especially if her great-grandchildren follow her example and live another nine decades. She was very strong until the end, even squeezing my mother’s hand so tightly a few weeks ago that my mother yelped in pain. On the morning after her death, an incredible blossom burst forth from the pygmy date palm tree by my front door, in precisely the same shade and pattern my grandmother had taught me to crochet.

Some of us have found comfort in the timing of her departure during (Orthodox Christian) Holy Week, or in making a donation in her memory to the Alkionedes Charity. Whether you believe in divine intervention or good karma, having her spirit on my side is my only explanation for how quickly and seamlessly my children and I were able to get from Delhi to Nicosia this week — not an easy itinerary, even in normal times — and that I was able to get my first Pfizer jab as a result.

We should be grateful that Yiayia Elli stayed with us for so long, as a long, strong connecting thread holding her loved ones together across time and space. From Cyprus to Seattle, New York, Miami, the British Isles, India and Sri Lanka, and wherever else we set foot in the years to come, we will think of her with admiration and a smile.

Thank you for reading.